My Friend Twiggy, & The Wrestlers Who Made Soho

Write What You Know - some indulgent autobiography

Write what you know, that’s what they always tell you. It’s a dubious bit of advice, often taken to mean not to write outside one’s experiences, rather than to use said experience to lend emotional weight and verisimilitude to even the most outlandish of situations - I don’t think Terry Pratchett knew what it was like to be a werewolf police officer, but he was all too aware of what it is to live in world threaded with absurdities and prejudices. Write what you know. It used to be remarked upon with astonishment that Arthur Rimbaud had never even seen the sea when he wrote “The Drunken Boat” but nor, I suspect, had he ever met a talking boat, and no one seems to find that unusual. Write what you know. It can be stultifying advice. I’ve always wanted to write, from as early as I can remember, I always have written, but that advice has led to many an abandoned project; doubts emerge, what right do I have to be telling this story, to be putting my words in these characters’ mouths? What do I know? What do I do? I work, I sleep, I read, I write, I go to the pub, and then there’s wrestling. Maybe there’s something in all that?

Now Jeffrey Bernard, there’s someone who made a career of writing what he knew. I recently revisited a collection of his Low Life column, spurred by on by having attended a production of Jeffrey Bernard Is Unwell at Soho’s Coach & Horses pub, where the entirety of the play’s “action” takes place, starring the delightful Robert Bathurst.

To the uninitiated, Bernard’s column was created to contrast the High Life column written by Taki Theodoracopulos - more famous these days for his vocal support of ultra-nationalist fascist groups, and for writing a 2018 Spectator article with the headline “In Praise Of The Wehrmacht” - and while the then-mononymous “Taki” wrote of jet-setters, yacht parties, and the highest of high society, Jeffrey Bernard wrote of alcoholism, horse-racing, his many divorces, and of days and nights spent in the pubs, clubs and gutters of London’s Soho. Bernard had previously been the racing correspondent for Private Eye after a varied career that took in everything from coal-miner to theatrical stagehand, and a stint in a job that wouldn’t be out of place in the early chapters of my book, Kayfabe: A Mostly True History of Professional Wrestling, as the resident pugilist in a carnival boxing booth.

Low Life was a book I first discovered in the Reference section of Jersey Library, where I spent many a quiet afternoon as a student, and later as a university drop-out during the intermittent periods of precarious employment, unemployment, and antisocial working hours that recurred, one way or another, well into my mid-20s. I was, in the manner of all young men who swallow William Blake’s lie that the road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom, exploring my own particular “low life” just as enthusiastically as I was expanding my literary horizons, believing that there was some wisdom or nobility to be found in the gutter. Following the same impulse that led me to the writings of the Beat Generation, Charles Bukowski, and Hunter S. Thompson, and to the music of Tom Waits and The Pogues, it was little wonder that I would pick a book off the shelves that celebrated the lifestyle of the habitual drinker and dosser.

Much of Jeffrey Bernard’s frame of reference was alien to me - aside from liking a drink, I lacked the life experience necessary to relate to his tales of divorce, tax debts and constant ill health, and I had never been to London, never mind Soho - yet still the world he described felt, in some way, appropriately, intoxicating.

At around the same time, I read the artist and fellow Soho eccentric Sebastian Horsley’s mesmerisingly obscene and witty memoir Dandy In The Underworld - bought on a whim for its title, and after expertly judging a book by its cover, it soon became a personal favourite. Unlike Bernard, there were parts of Horsley’s world that I could unexpectedly relate to - a shared hometown anchored the stories of his childhood in a geography I understood, a mutual love for glam rock and post-punk music placed him in a familiar cultural context, and as a young man recently enamoured with the writing of Oscar Wilde, experimenting with more flair and flamboyance in my dress sense and taking an interest in the endless rules and conventions that dictate men’s fashion, the musings of such an arch-dandy were like catnip to me.

The final piece of a puzzle I didn’t know that I was trying to solve was an unlikely friendship. A few doors down from the library was a coffee shop, in those days the sort of place you could go and reliably know somebody at any hour of the day if you fancied a chat, but where I was usually content to sit and lose myself in a good book for an hour or two. The small outdoor smoking section created, as smoking sections tend to do everywhere, unlikely friendships and cross-cultural exchanges between people with little in common bar all being wont of cadging a cig or a lighter. Among the same old familiar faces, those outside tables had recently acquired a new habitué, an enormous figure of a man in his early fifties, though he could have passed for much older, standing over six foot tall and weighing at least 25 stone, clad invariably in tweed and corduroy, he would take up residence outside early in the morning, and stay there until closing, chain smoking at a prodigious rate, making conversation with anyone and everyone who would listen, throwing scorn on his fellow members of a nearby public school Old Boys’ club, and occasionally apologising when he had to (with considerable effort) rise from his chair to wander up the street while he took a call on one of two ever-present mobile phones. He seemed to me to be monstrously posh - not a rarity in Jersey, an island ruled by public school ties, who-you-know politics, and the vagaries of the offshore finance industry - and, quite cruelly, a couple of my friends gave him the nickname “Uncle Monty” after the theatrical and predatory old queen played by Richard Griffiths in Withnail & I. In later life, after growing a beard, he would, by his own admission, come to more closely resemble Orson Welles.

His quick wit, and his knack for making anyone he engaged in conversation feel like a privileged co-conspirator in rarefied company (once, if you’ll excuse me fast-forwarding in time a few years for an aside, he was chatting to my then-girlfriend for the first time; she had been daunted and a little nervous at the prospect of meeting him, and he put her at ease when, after hugging and saying hello to a passing friend, he leaned in and conspiratorially whispered in her ear by way of explanation, “she had the misfortune of having been married to Sean Bean”), meant that he developed what must have looked to passers-by like an unlikely revolving door of friends - mechanics in the morning, ultra-camp Portuguese hairdressers on their lunch break, a hulking former New Zealand paratrooper-turned-martial arts instructor and personal trainer in the afternoon, and a smattering of skaters, punks and assorted layabouts in the evening, including a long-haired, emaciated goth kid and aspiring DJ who hadn’t yet started pretentiously insisting on styling his name with a middle initial, but who would one day be Patrick W. Reed.

Though in Jersey I knew him by his real name, this man always preferred the nickname Twiggy, bestowed upon him by the late Muriel Belcher, the fearsome landlady of the legendary Soho dive the Colony Room, and out of respect that is the name I will use to refer to him from hereon in.

My Friend Twiggy

I was lost and directionless as all but the most insufferably smug early 20-somethings are, and, already accustomed as I was to bouncing between pubs and conversing with all manner of barflies and bores, and, in the manner of young people everywhere, thinking myself infinitely more worldly and knowledgeable than I was, I saw nothing overly unusual in a growing friendship with a man some thirty years older than I was. I was lucky, in those directionless days, to meet a few people who took an interest in me and wanted to see me achieve more than the path that my life had set me down, and Twiggy was chief amongst them. His gestures of support were small, almost invisible to everyone but their beneficiaries, and that is how he liked it, but to me they were invaluable - slipping me a tenner when I couldn’t afford the entry fee for a gig, or sending me up to buy him a coffee and allowing me to keep the change, always enough to at least buy myself a pint later - though it was his conversation that was the real key to unlock what he envisioned for me.

His anecdotes were well-worn but well-delivered, and he could namedrop like no other. Francis Bacon was the most frequent recurring star of his stories, with walk-on parts for everyone from Tom Baker to William S. Burroughs to Lisa Stansfield, and, from Twiggy’s time living in the United States, there were stories of attending poker games with the novelist John Updike, whom he lived down the road from, having rented a palatial seven-room house sight unseen from a bloke he met in a bar. Most enticingly of all to me then, he knew Sebastian Horsley, and had known Jeffrey Bernard well - he often spoke adoringly of the first production of Keith Waterhouse’s play, the aforementioned Jeffrey Bernard Is Unwell, with Peter O’Toole in the title role, and loved explaining that the source of the title was the notice that was printed in The Spectator every time Bernard had been too drunk to submit his column on time.

One wondered why this man who, according to his stories, once rubbed shoulders with the great and the good of 20th century art and culture was reduced to taking inscrutable phone calls outside a Jersey café. Of course, there was always the slight nagging suspicion that it could all be bullshit. Over time, as I got to know Twiggy, I learned where he lived - a tiny, somewhat ramshackle flat above the stockroom of British Home Stores, which I coincidentally knew well, having been friends with its former occupant; it was in the bathroom of said flat that I first dyed my hair and where, in lieu of a couch, we sat on ripped out car seats on the living room floor. It didn’t seem to befit the man behind the anecdotes.

The answers became clearer as I got to know Twiggy better. The first time we went for a drink together was at my favourite local pub, The Peirson, following a flash-mob public pillow fight in the town square - and if that doesn’t date this story to 2006, nothing will. It turns out that when you’re drinking with a man once described by the Daily Mail as “a twenty-something stone trencherman who drinks Port by the pint”, and he’s the one buying the rounds, drinking a pint of Guinness to every one of his glasses of red wine makes for an interesting evening, but not one I was in a hurry to repeat.

It was over the course of that long evening drinking with Twiggy that I was able to begin piecing together the parts of his life story, or at least the parts he felt comfortable letting me into; other aspects took years to piece together. He had family in Jersey, and he had returned there following a bankruptcy that saw a net worth of millions collapse, leaving him with less than a hundred pounds in his bank account. After initially bouncing around Soho, he headed for Jersey, reliant on the charity of his brother and the old boys’ network while he pieced his life back together. During that same conversation, he began what would become an insistent theme - his belief that I needed to leave the island and find my way to either London or Amsterdam, his other favourite place in the world, to make something of myself.

In time, Twiggy left Jersey, only returning occasionally for family events or to see his doctor, every time presenting the need for a few drinks and a much needed catch-up. As those visits became less frequent, our meetings moved to London - the first time I was in the city for a gig, as he was unable to be there, he presented me with a letter of recommendation to allow me into the Colony Room should anyone try and refuse me entry, but once the Colony shut its doors, it was always the French House where we would meet, where he would be at his most unguarded, and where he would occasionally snap at me whenever I dared buy a round behind his back. It was there that he spoke the immortal line about Sean Bean, where he first brought up the subject of his sexuality and the story of him first feeling able to come out of the closet in Amsterdam in his mid-30s, and where we had the most meaningful of our conversations, and the most eye-opening of our nights out together.

One time, when asked what I was doing in London, I felt a little apprehensive about telling Twiggy I was there for a wrestling show. Wrestling felt too low rent for this environment, for this man, and, still young and unsure of myself, I was afraid of disappointing someone who had invested so much hope in my future prospects. I needn’t have worried - far from laughing it off or even raising a quizzical eyebrow, in a flash Twiggy introduced me to the man sat next to him at the bar, a trustee of the Royal Variety Charity, who oversaw their Brinsworth House nursing home. One of his favourite residents, as it transpired, was a then-91 year old Mick McManus. My grandad’s favourite wrestling villain and, as local legend would have it, one-time landlord of the New Cross House in my current South-East London stomping grounds. Everything is connected.

Several thousand words in, you must be wondering why on Earth I’m subjecting you to all this personal reminiscing and mythologising, and when I’m going to get to the subject of professional wrestling beyond a walk-on cameo from the ghost of Mick McManus. Don’t worry, I’m getting there.

A Psychogeographical Jaunt; or a Pub Crawl

Up the road from the French House on Dean Street was the former home of the Colony Room, where the great and good got pissed up, swore and threw up on the floor, and where my old friend stumbled coming up the stairs on his first ever night in Soho, crashing through the door to be greeted with a call of, “who’s this fat cunt, then, Twiggy?”, the indomitable Muriel Belcher bestowing him with a name that would follow him for life. So the story goes, he had run away from school aged fifteen and used his dad’s account to pay for a Taxi to London - asked where to go, some gut instinct made him ask for Soho, and he entered the first pub he came to, the Coach & Horses on nearby Greek Street. There, the future Twiggy was bought drinks by Jeffrey Bernard, glad of the company, though Twiggy initially assumed the older man was trying to proposition him. Twiggy was reluctant to accept Bernard’s offer of a drink, explaining that he was only a schoolboy and couldn’t pay him back - Bernard laughed off his excuses, and said that in Soho, you bought rounds when you could afford them, and were bought them when you couldn’t, a philosophy Twiggy often reiterated the importance of. Today, the Coach & Horses remains haunted by Jeffrey Bernard, dead since 1997. Aside from his titular play being performed there, and posters of previous productions adorning the walls, cartoons and caricatures are all over the place - if not of Jeffrey himself, then of others speaking the pub’s unofficial catchphrase, “Jeff bin in?”.

Stumbling out of the Coach & Horses and back over to Dean Street, as thousands of eager drinkers have before me, and resisting the urge to return to the French, it’s easy to miss amid the swanky eateries and lookalike chain stores what was once not only the heart of Soho decadence, but also the beginning of a story about the debts that Soho owes to professional wrestling. Finally, the readers cry, he got there.

The Wrestlers of Dean Street

It was here on Dean Street that the ghost-written autobiography of former blog subject Eric “Panther” Pleasants places the wrestling gym of Greek Cypriot wrestler and entrepreneur Costas Astreos, though given that the book manages to badly mangle Astreos’ name to the point that it took me longer than I’d care to admit to realise who or what he was talking about, and that said ghost-writer was Eddie Chapman, a World War 2 double-agent and long-time petty criminal with a penchant for tall tales and stretching the truth to breaking point, I doubted whether said gym, which Pleasants/Chapman populates with just about every heavyweight star of the 1930s, even existed. It seemed just as likely that, tasked with developing a backstory, Chapman plucked some names out of the headlines and the show bills in that day’s newspaper, and placed it in familiar territory, given that Eddie Chapman was no stranger to Soho himself. But Dean Street’s wrestling history neither begins or ends with that dubious connection.

Allowing ourselves a sombre glance at what was once the Colony Room, next door your eyes may be drawn to a French Brasserie - here, too, was once a drinker’s den, the Caves De France. Were you to have poked your head through the door in the 1950s, you might have spotted the photographer and long-time chronicler of old Soho John Deakin, shunned from the Colony, being served a drink by barman Secundo Carnera, the brother of legendary boxer and wrestler Primo Carnera (unimaginative parents seemingly deciding that numbering their sons would be easier than naming them). When not behind the bar, Secundo worked in, and lived above, an Italian restaurant where now the ultra-trendy Groucho Club stands, and was alleged to have connections to the Italian gangs that then ruled over much of Soho. Not the first wrestling-adjacent figure to enter London’s murky underworld, and far from the last we will be meeting today.

Just before the turning on to Meard Street, where the basement flat that once belonged to Sebastian Horsley is now, in the ultimate final gentrified nail in old Soho’s coffin, an Airbnb, the sign proclaiming “This is not a brothel: no prostitutes live at this address” long since removed from the front door, we arrive at the Dean Street Townhouse, a self-consciously glamorous and ostentatious restaurant and hotel well outside of my price range. It wasn’t always thus, though - back in 1982, this was the original home of The Batcave, the birthplace of English goth, a makeup and glitter-spattered weekly club night that brought together London’s disparate musical subcultures, gave freaks and weirdos a dance-floor of their own, and birthed a thousand genres of music. But 69 Dean Street’s reputation as the place for gender and sexual experimentation and deviant dancehall antics goes back even further, with another suitably gothic name; it was once the Gargoyle Club, opened in 1925 by aristocrat David Tennant (not that one).

The Gargoyle arguably created one of the lenses through which Soho likes to see itself - combining a ballroom, a coffee lounge, rooftop garden and dining room, this was the height of Roaring Twenties opulence; interior design by Henri Matisse, an in-house jazz band, and an audience that mingled London’s bohemian art scene with the most aristocratic of aristocrats - Dylan Thomas, Francis Bacon and Lucien Freud rubbing shoulders with Rothschilds, Royals and Lords and Ladies, missing only the criminal element that would give post-war Soho the frisson of excitement and transgression it made its reputation on. That’s not to say there wasn’t plenty of rule-breaking going on - as something of a home base and a place to be seen for the “Bright Young Things”, the Gargoyle was a hotbed of drinking, drugging and debauchery, of gender-play and sexual experimentation between the wealthiest inhabitants of London’s gossip columns; at a time when homosexuality was still illegal, what was criminal for ordinary working people was often merely scandalous for the rich and titled.

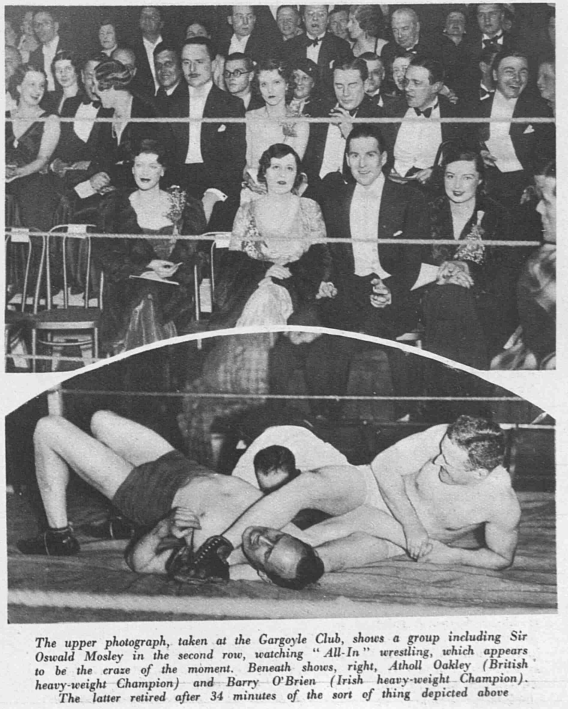

One aristocrat who does not seem to have been a member of the Gargoyle Club did make at least one unlikely appearance there, however, and that is Sir Atholl Oakeley. Oakeley, as readers of Kayfabe will know, was instrumental in transforming British wrestling in the interwar years, building on the growing rough-and-tumble style popular in America with what he called “All-In Wrestling”. In an industry built on gimmicks and jingoism, for decades almost every Brit who crossed the Atlantic saw fit at one time or another to pop on a bowler hat and monocle and style themselves “Lord” or “Sir”, but Oakeley really was the real deal, a genuine “Blue Blood” as he styled himself, the 7th Baronet of Shrewsbury. In 1932, presumably at the behest of club owner David Tennant (still not that one), Oakeley began putting on All-In Wrestling exhibitions in the ballroom of the Gargoyle, featuring himself alongside the top stars of his stable, including “The Doncaster Panther” Jack Pye, and Irish Champion Barry O’Brien. By all accounts wrestling was an unlikely hit among the socialites and well-to-do, and photographs from those events make for surreal viewing - the audience in full evening suits, glamorous ball gowns and furs, while wrestlers struggle on the mat. In one photo, the fascist leader Oswald Mosley stands in the second row, an inscrutable expression on his face.

Mosley would not have been short of admiring company - for a time, the Gargoyle counted among its members the Nazi collaborator John Amery, whose concept of a British Nazi legion led in part to the creation of the British Free Corps, the branch of the SS of which our old “friend” Eric Pleasants was a member. If Pleasants, or Eric Chapman’s pen putting words in Pleasants’ mouth, is to be believed, the former “Panther” even had an affair with Amery’s wife in Germany. That’s not to say the other side of the political spectrum wasn’t well represented in their membership, though - other members including at least three of the Soviet double agents of the Cambridge Spy Ring; Kim Philby, Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean, along with the hard-drinking and controversial journalist, future Labour MP, and alleged Communist spy Tom Driberg. Amid an extremely colourful and tumultuous life story, Driberg had been a friend and sometime collaborator with the occultist - and fellow Gargoyle Club member - Aleister Crowley, himself a fan of All-In Wrestling, which in his diaries he pleasingly described as, “three hours of sweetness and light”.

The Inevitable Appearance of George Hackenschmidt

One wonders what one of Atholl Oakeley’s heroes must have made of it all - that hero being, of course, George Hackenschmidt (if you’ve read my work before, you had to know he would show up eventually). Walking further up Dean Street, we pass an innocuous street corner; here, opposite what is now the Soho Theatre, is where Gene Tierney hailed a cab in the film noir classic The Night And The City, the story of a con-man and hustler’s efforts to ingratiate himself into London’s seedy underworld through fixing wrestling matches. The role of aging wrestler Gregorius Kristo is played by a gloriously craggy and weather-beaten Stanislaus Zbyszko, the then-71 year old Greco-Roman star who had been a headline act on both sides of the Atlantic from the early 1900s to the mid-30s, was heralded as one of the all-time greats, and in retirement trained the legendary NWA World Heavyweight Champion Harley Race. The role wasn’t always intended for Big Stan (as nobody has ever called him), however - it almost went to George Hackenschmidt, and an ensuing bit of press coverage led to a lawsuit from our George; when the News Review playfully suggested that Zbyszko had, in winning the role, “beaten” Hackenschmidt for the second time, Hack successfully took them to court for the implication that he had ever lost a match to Zbyszko!

It would be a short wander, a little off our route, down to Lower James Street, where Hackenschmidt lived for a time between the wars, before returning to France to be with his wife - disastrously finding himself caught up in the wrong place at the wrong time in his second war, having spent the First World War interred in a German camp. From Lower James Street, Hackenschmidt wrote numerous daunting and incomprehensible books on his baffling brand of philosophy, having faced indignity and inhumanity during the war, Hack turned his attentions to matters spiritual and psychological, disavowing his earlier works prioritising development of the body as the sine qua non of personal health, and preaching distrust of any dogmatic or one-size-fits-all training system. Many of his ideas were extraordinarily silly, while others - like his early criticism of the growing National Socialist movement in Germany - were anything but, and it’s easy to see how he was, for a time, taken seriously as a potential great thinker, heralded by George Bernard Shaw and invited to lecture at Trinity College, Cambridge in the 1930s. It’s tempting to picture the Russian Lion crossing paths amid the dreaming spires with some of the Cambridge Five, the Soviet spies who would ingratiate themselves into the very highest positions of English statecraft, and drink themselves silly just a hop, skip and a jump away from the sober Hackenschmidt’s London pad.

Just one road over, in his Frith Street lodgings, Israel Karp passed away aged 50 in 1926. The name means little to anyone, but to the wrestling fans who queued up in the early 1900s to watch George Hackenschmidt wrestle, he was better known as Charles Herman; a regular Hackenschmidt opponent, sparring partner, and preliminary match worker, in the days when theatrical impresario Charles B. Cochran was shopping The Russian Lion around the theatres of London, often expecting his chosen champion to work upwards of three matches a night. A 1906 Sporting Life account account of a match between the two men was the first mention I’ve seen of Cochran, who would go on collaborate with Noel Coward and to manage the Royal Albert Hall, working as the referee for one of Hackenschmidt’s matches.

Poor Israel Karp wasn’t the only former Hackenschmidt running buddy to set up shop in Soho, however. If we allow our stumbling, easily side-tracked walk to take us down to Gerard Street, in what is now part of Chinatown, an unassuming Chinese hairdressers and beauty salon occupies a property that was once the home of Hackenschmidt’s one-time trainer, long-time rival, and fellow countryman, Georg Lurich. The other Estonian Georg was a champion weightlifter and Greco-Roman wrestler, who befriended Hackenschmidt in 1896; he became a mentor and training partner to the then-teenage Hack, but the success of his young protégé overseas caused Lurich to resent Hackenschmidt, and try to dog him at every turn. For years to come, Lurich promoted himself as “The Man Who Beat Hackenschmidt”, resting on the laurels of a sparring mat victory over a then-untrained teenager who was now being heralded as unbeatable. He followed Hackenschmidt around the UK and the United States, and in 1904, from his Soho townhouse, found himself summoned to court on charges of threatening and extorting money out of the promoter of an upcoming George Hackenschmidt/Tom Jenkins World Title fight at the Royal Albert Hall, claiming Hack’s claim to the title was bogus, that the fight was a fix, and that Lurich himself was the only deserving contender. While the courts agreed that Hackenschmidt and Jenkins were on the up and up, the case was thrown out. Lurich himself came to a messy end - travelling with fellow Estonian wrestler Aleksander Aberg, the two were caught up in the Russian Civil War and, stranded in war-torn Armavir, with medical aid in short supply, both men succumbed to typhoid and pneumonia within weeks of one another. They were buried in a single grave.

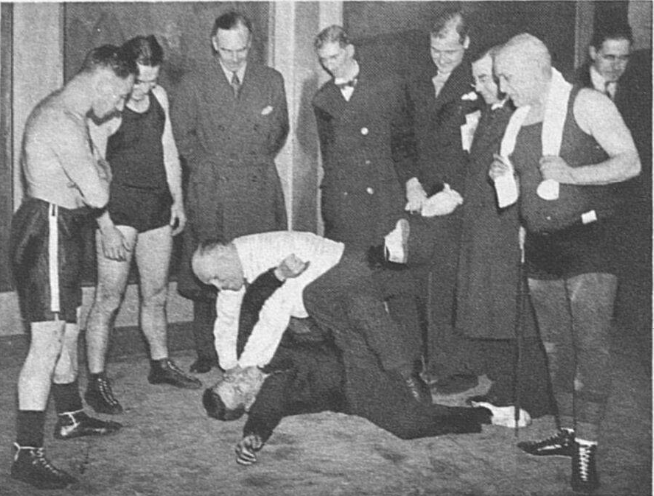

Eric Pleasants may or may not have grappled on the grimy mats of a Soho gym, but George Hackenschmidt certainly did. In 1932, old George was one of a group of wrestlers and other athletes entrusted to coach MPs in “physical culture” and fitness, with an aim to opening a private gym for members of both houses. Among those names present that newspapers saw fit to publish were the Liberal William McKeag, Labour’s Tom Williams, and the Tory Edward Doran, who only one year later would take a stance entirely at odds with what we know of Hackenschmidt’s personal politics, publicly calling for Britain to refuse to allow in any Jewish refugees; in the days leading up to the outbreak of World War 2, Doran’s antisemitism would only intensify; he threatened to leave the Conservative Party and stand as what he called a “National Imperial Patriot”, formed an explicitly pro-Hitler activist group he named “The Liberators”, and was repeatedly rebuked by his North Tottenham constituents for his fascist leanings. Below, he is pictured unsuccessfully grappling with Hackenschmidt - the Russian Lion was, at least by 1935 when he wrote of the subject in his otherwise largely incomprehensible book Man and Cosmic Antagonism to Mind and Spirit, proudly anti-Nazi and anti-fascist.

Of Gangsters and Grapplers

From one Nazi to another, another Soho resident was Karl (or sometimes Carl) Reginsky, a wrestler, part of Atholl Oakeley’s regular stable, who was an early adopter of a persona and gimmick that was to become commonplace in the post-war years - accentuating a face disfigured by a long scar, Reginsky shaved his head and began goose-stepping to the ring in a robe laden with Swastikas, presenting himself as the champion of Nazi Germany in 1939. But as you might have guessed, Reginsky was no Nazi, and only slightly German - he was born Casimir Raczynski in London, to Polish and German parents. He was the subject of a 1938 legal case referred to in chapter 2 of my book, when a referee sought damages for an injury at Reginsky’s hands - the law took a dim view of the affair. Outside of the ring, the law wasn’t any fonder of him, and with good reason - he operated the Phoenix Club out of Little Denmark Street, where Reginsky’s brother was arrested for assaulting a patron and a waitress with an iron bar; despite taking place in a crowded nightclub, not one witness came forward. In 1931, caught in the middle of a gang war between the Sabinis and the Whites that would ultimately see the Italian gang forced out of much of West London, a member of the Whites cut Reginsky’s throat and slashed his face as he walked out of his own club. In a spectacular case of making lemonade when handed one of life’s lemons, in a few years’ time Reginsky was able to claim it as a duelling scar when reinventing himself as a Nazi. Only in wrestling!

In one of the more distasteful moments of Reginsky’s career, he occasionally worked matches against an Estonian wrestler named Samuel Burmister, who styled himself as the World Jewish Wrestling Champion. While Reginsky was a phony Nazi, Burmister was a decidedly genuine Jew, who took the opportunity of an international professional wrestling tour to escape the rising antisemitism of inter-war Russia - he eventually settled in Australia, but not before spending a few years wrestling and touring the music halls around England. In the halls and on the stage, he was an acrobat and strongman, one half of the double act “Nello & Mello” alongside Giovanni Periglione, an enforcer for the Sabinis. In time, Periglione would leave the act, replaced by one Bert Assirati.

Bert Assirati might be a name you recognise - it carried a legendary pedigree for generations of British wrestlers; those who risked getting in the ring with him spoke of a mean streak and propensity for hurting his opponents married to superhuman strength and exceptional technical skill that made him as formidable an opponent as you could find, even in a worked sport, while those who grew up watching him revered him as an idol, and listened in awe to stories of his success. Adrian Street, who was never quick with a compliment for another wrestler, spoke of him as the best he had ever seen.

From his earliest days as a wrestler, Bert Assirati was turning heads, attracting the attention of wrestler-promoters like Atholl Oakeley, Henri Irslinger, and William Bankier with his combination of Wigan Snake Pit-honed catch-wrestling skills and the kind of prodigious feats of strength he had mastered at the music hall - so much so that George Hackenschmidt sought him out and advised him to give up the wrestling game altogether and focus on strength training, as Hack felt Assirati had potential to become the strongest man in the world.

While Assirati’s star shone brightest in England, he competed all over the world, against almost every major star of his generation - Lou Thesz was one notable exception, with Assirati claiming that Thesz ducked him at every opportunity, while Thesz wrote in his autobiography that it was quite the opposite, Assirati refusing to work with the then-NWA World Heavyweight Champion during one of his rare trips to the UK. By that point, in the mid-1950s, Assirati’s career was on the decline. British wrestling was changing, with Joint Promotions holding the reins of power, and Mountevans Rules the new game in town - the rough and violent Assirati was a poor fit for what tried to sell itself to the public, and more importantly to anyone with an interest in regulating and reforming the sport of wrestling, as a cleaner, more gentlemanly approach to the mat game. With Assirati proving difficult to do business with, refusing to cooperate with opponents or take losses to anyone he felt he couldn’t legitimately defeat (and, when you’re Bert Assirati, that’s almost everybody), the most powerful promoters in the country cut their losses and let him fade into relative obscurity. He held titles, but the committees simply stopped recognising him as champion. When Joint Promotions chose a young Shirley Crabtree, then the “Battling Guardsman” but later to become the rotund hero of British TV wrestling Big Daddy, as Assirati’s successor, Bert was so appalled that he hounded and harassed both Crabtree and his promoters, causing enough of a nuisance to force young Shirley into early retirement, prior to his subsequent career reinvention as an avuncular hero to children clad in gear famously made from his wife Eunice’s chintz sofa.

Bert Assirati’s wrestling career stumbled to an end in 1960 or thereabouts, reduced to working small independent shows far from the bright lights of television, and he turned to working as a bouncer, with one stint landing him on the door of La Discotheque in Soho’s Wardour Street; nicknamed “The Disc”, it was the first club in London to play only recorded music with no live band, and its playlist of soul and R&B hits made it a huge draw for the mod crowd - as did its reputation as the centre of the trade in Purple Hearts, the stimulant of choice for the swinging sixties. With the likes of the Kray Twins muscling in on the Soho nightclub scene, club owners needed a man of Assirati’s abilities on the doorstep - one night in 1963, when Assirati was apparently encouraged to take the evening off, his replacement for the night was shot in the leg after refusing two men entry. Assirati himself had been stabbed while on duty on at least one occasion, and wrestling legend is that he subdued the perpetrator and handed them over to the police with the knife still sticking out of him.

These were, it seems, fairly routine occupational hazards. The 22-stone Ian “Bully Boy” Muir was stabbed and shot in both legs while working the door of the Candy Box; this was a club that opened at 3am and closed at 7am, ostensibly so the staff of other clubs had somewhere to drink when they clocked off, but with those opening hours, the clientele was what you might call eclectic. Being stabbed, slashed and shot didn’t seem to hold old Bully Boy back - he stepped into the relative safety of the wrestling ring three years later, and made his television debut in 1975. He picked up a couple of acting jobs, playing a giant in Time Bandits and a wrestler in the Brian Glover-penned episode of Theatre Box “Death Angel” as a wrestler alongside Ray Winstone and Bill Maynard; in case you were wondering, that means Ian Muir makes it only two degrees of separation between Akira Maeda and Greengrass off of Heartbeat. As for Brian Glover himself, he had been one of British wrestling’s finest ever comedy acts, his unmistakeable Yorkshire accent not preventing him from billing himself as “Leon Arras, The Man From Paris”.

Back to Bert Assirati, though, because his work in Soho wasn’t all on the doorstep of the Disc. The owner of that nightclub was the notorious slumlord Peter Rachman. It was living through internment in one war and the Nazi occupation of France in the second that inspired George Hackenschmidt to pursue the fields of Psychology and Philosophy, and to dedicate the rest of his life to, in his own esoteric fashion, attempting to solve the spiritual and existential problems facing mankind; unfortunately for the people of London, internment in both Nazi German and Soviet labour camps during World War 2 taught Peter Rachman no such empathy. Soho will be Soho, so it perhaps comes as little surprise that he started his property empire by securing rooms for prostitutes, eventually expanding to a network of homes, hotels, and nightclubs, run through an impenetrable network of shell companies, and rife with exploitation and corruption. Rachman’s name became a byword for the threatening, victimisation and exploitation by unscrupulous landlords, while business dealings with the Krays and a walk-on part in the Profumo Affair - one of a series of sex scandals with potential national security implications that played a part in costing the Conservative Party the 1964 General Election - only added to his notoriety.

Any slumlord needs their heavies, and Peter Rachman was no exception. Whether through employees like Bert Assirati, or through the Legitimate Businessmen who found their way backstage at wrestling shows in London with offers of an extra payday if a chosen wrestler would just do a few odd jobs while they’re in town for a match, a few grappling stars took their brand of violence from the ring to the streets in service of Peter Rachman.

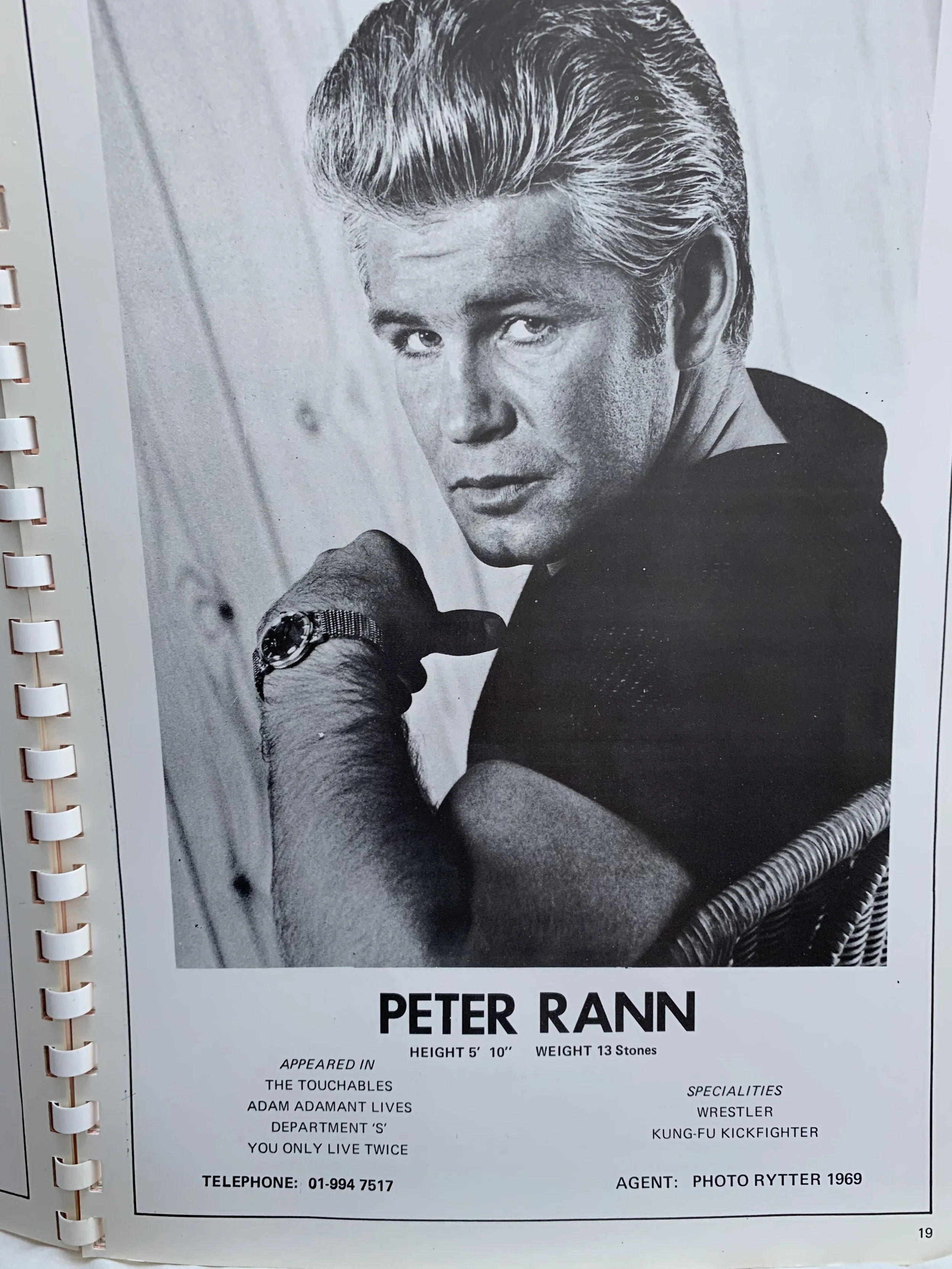

One, the strikingly handsome Peter Rann, was known inside the ring for a brutal double knee stomp, and for wearing a streak of blue dye in his hair. Outside of the ring, he was a volatile wild-card who practiced taking falls on the concrete in Hyde Park, who was never shy of pulling out a knife when backed into a corner, and always happy to fight. In 1972, a match with Les Kellett that had been taped for the Saturday afternoon “World of Sport” TV slot ended up having to air after the watershed on the following Wednesday because it turned so bloody and violent, with Kellett being handed a rare count-out loss to Rann - given Kellett’s popularity and political clout, and the rarity of his TV losses, a defeat of that nature to a relative nobody like Rann has for some years raised the question of the match having turned into a shoot or legitimate fight, or of Rann having been put up to the task of putting the frighteners on Kellett on behalf of another wrestler/promoter, with most who buy into that particular conspiracy pointing the finger at Mick McManus. To anyone who has heard the countless stories of Les Kellett’s inhuman toughness, the thought of a wrestler capable of leaving him a bloody mess is a scary prospect indeed!

With credentials like that, it’s little surprise that Peter Rann was a prime candidate for work as a debt collector for Peter Rachman. Rann’s running buddy in the intimidation game, responsible for forcibly evicting tenants, was another wrestler, the inimitable Norbert Rondel. Abandoned by his father following the death of his mother, the Jewish and Berlin-born Rondel arrived in Britain on the Kindertransport, and settled in Manchester, where he studied to become a Rabbi. His spiritual ambitions were unrealised, however, and Rondel fell on hard times, and, after a stint in psychiatric care in South London, while working as a gardener, his passion for fitness and weight-lifting took him into professional wrestling, though like the equally eccentric Great Antonio it took him time to appreciate that the objective was not to actually injure your opponent - it took a particularly heavy-handed lesson from Bert Assirati to teach him that, and the two men became regular opponents, perhaps because so few others wished to wrestle either one of them! In time, Rondel would come to replace Assirati on the door of La Discotheque, and even to run his own nightclub, The Apartment, on Rupert Street, which runs parallel to La Discotheque’s Wardour Street.

In the wrestling ring, Norbert Rondel was “The Polish Eagle” Vladimir Waldberg - though, if the Polish-born Peter Rachman were in attendance, he went by “The White Eagle” instead. It was a short-lived career, if only because Rondel was in and out of prison and courthouses for most of the 1950s and ‘60s; in 1959, he even attempted to sue his own barrister for professional negligence in not defending him to the best of his abilities on a charge of grievous bodily harm - the sticking point for Rondel was that he had been charged with cutting his victim’s ear, when he had in fact bitten half of it off! The man who was known to many as “Mad Fred” Rondel took his appeal all the way to the House of Lords, but it wasn’t until 2002 that the law was changed to allow litigants to sue barristers for negligence.

After Peter Rachman’s death, his empire began to crumble. Norbert Rondel again found himself in court in 1963 for threatening fellow club owner and former Rachman debt collector Serge Paplinski, and placed the blame on Peter Rann for framing him, after the former Polish Eagle had sold his story to the press in light of the Profumo Affair making Peter Rachman gossip briefly a highly sought after commodity.

It was in these post-Rachman years, and as the Sixties ticked over into the Seventies, that Rondel opened The Apartment and became a Soho celebrity in his own right, though never far from violence, controversy, and criminality. In 1976, he was held on charges of conspiracy, accused of having arranged the robbery of a Knightsbridge Spaghetti House restaurant that went badly wrong and turned into a six-day siege when the police arrived on the scene and the perpetrators barricaded themselves in the stockroom, taking staff members hostage. Rondel’s role was negligible - he was never the “criminal mastermind” type, and the suggestion that he arranged the whole thing on a tip-off from an employee who owed him money doesn’t ring true, not least of all because the three robbers involved were all members of black liberation groups and made clear political demands of the police during the siege; though the police largely discredited the idea that they were motivated by anything more than criminal gain. Eventually, Norbert Rondel did settle down somewhat, and became an avid chess player, and a used car salesman in South London. Peter Rann, meanwhile, abruptly retired to Blackpool, leaving Soho behind, with a trail of suggestions of having got on the bad side of the wrong people.

I daresay we have done our time on Wardour Street, so as we walk past what is now a fairly dismal chain pub and swing left on to Gerrard Street, if we were to step back in time to the 1960s and ‘70s we may here have encountered one of Soho’s strangest denizens, and yet another of the wrestlers who made Soho. Because here, Royston Smith allegedly ran a club exclusively for dwarfs.

Little Legs, the Muscleman of Soho

Royston Smith was born to a Romani-Jewish family, and was deaf and dumb until the age of seven, still instinctively resorting to sign language when under stress until the end of his life. At 4’2”, and faced with an interlocking matrix of prejudice and suspicion from the world around him, life was never going to be easy for him, and he had to live by his wits. His life - documented with rather too much credulity in a biography by former Tory MP and NME hack George Tremlett - had skirted on the edge of criminality since his youth, and by the 1960s, going by the nickname “Little Legs” (not to be mistaken for the present-day 4’ wrestler of the same name), he had found his way into Soho’s underbelly as everything from thief and safecracker to pimp and unlikely intimidation merchant; Tony Mella, the Soho gangster and former boxer murdered outside the Bus Stop strip club on Dean Street on 28th January 1963, had apparently been knifed across the backside by Little Legs in a previous altercation.

But there was a glamorous side to Little Legs too; his height and apparent charm made him an obvious candidate for roles in pantomime, and under the name Little Jimmy Kaye, he became a regular in music hall, circus, and end of the pier entertainment shows, and a bit part actor in films and TV. He played a trundling robot called a “Chumbley” opposite William Hartnell in a Doctor Who serial, and appeared in The Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour, though his boasts of having also appeared alongside the likes of Burt Lancaster, Kirk Douglas and Marlon Brando remain unverified, and his claim to have played the titular “Terror” in the famously awful all-dwarf musical western The Terror of Tiny Town is, quite simply, bullshit; aside from that role being performed by the veteran American actor Little Billy Rhodes, the movie was released in 1938, more than a decade before Little Legs first claimed to have visited the United States and when, if estimates of Smith’s age are correct, he would have been just seven years old.

Bullshit is a recurring theme when it comes to Little Legs, and all of the unsavoury characters we’re meeting on this journey. When your primary sources are wrestlers, criminals and drunks, honesty is in short supply. These are worlds where tall stories are the accepted currency, and where such trivialities as real names, nationalities and dates of birth are fluid and ever-changing.

When Royston Smith recounted his life story to George Tremblett, he was a homeless alcoholic, and towards the end of his life, getting by on the money he made busking and drumming up donations for other street performers. He recounts stories of drinking with Richard Burton, of daring criminal enterprises, and of being a close confidante and reliable ally of the Kray Twins; all of which has been recounted unquestioningly in countless cheap books on London’s over-romanticised gangsters of old. While Smith undoubtedly had gangland connections and a mean streak, George Tremlett’s claims to have verified as many of Little Legs’ stories as possible doesn’t ring true, and after Smith’s death, no less an authority than “Mad” Frankie Fraser called him unreliable, while the Krays’ older brother Charlie called the stories “the biggest load of rubbish” he had ever heard. In 1990, members of Smith’s family even rejected the suggestion that they were of gypsy stock, or that their family had ever lived in a caravan; a suggestion supported by earlier accounts by Royston Smith of his life story prior to George Tremlett’s book.

Writing this while awaiting the results of the London mayoral election, it’s difficult not to look at the state of our modern political class and pine for better days. Take, for example, this opening line of a Guardian article about Royston Smith’s nephew from December 1999;

“Tory London mayor hopeful Andrew Boff yesterday admitted his uncle was a wrestling dwarf who played a Dalek, but denied he was a henchman of the Krays.”

We used to be a proper country. But then, who do you find more trustworthy, a criminal drunk wrestler, or a Tory MP?

So maybe Little Legs wasn’t a gangland enforcer who hob-nobbed with the biggest stars of stage and screen, and claims that he managed the Kismet Club - a basement dive nicknamed “The Iron Lung” - or the elusive and possibly non-existent Midgets Club may be just as unlikely, but he did act alongside The Beatles, he did appear in Doctor Who, he did marry a showgirl, and he was indeed a “wrestling dwarf”.

In the account he gave to Tremblett, Royston Smith claimed that he had been invited to the United States in 1948 or ‘49, when his agent offered him work as a “midget wrestler”. There he claimed to have mimicked Gorgeous George by dressing in silk and sequins and bleaching his hair peroxide blonde while also, for reasons unexplained, keeping a pig on a leash. He spins an extraordinary yarn of touring alongside three other midget wrestlers - Tiny Tim, Sky Low Low and Little Beaver - but the tour being brought to an abrupt end when Sky Low Low strangled Little Beaver; left unsaid in the book, but implied elsewhere, was that this was a murder. The problem with this account is that Little Beaver continued wrestling well into the 1980s.

It’s enough to cast doubt on whether Little Legs ever went to the United States at all. Generously, he could be indulging in a spot of kayfabe here, as when he took to wrestling rings in the United Kingdom, it was under the name “Fuzzyball Kaye from the USA”, and he was generally billed from Ohio, perhaps to add a flair of exoticism, or even a strange kind of legitimacy, “midget wrestling” being an established undercard attraction in the United States in a way that never quite took off on this side of the Atlantic. Invariably competing against “Tiny Tim/Tom/Tommy” - real name Tommy Gallagher, apparently a discovery of Smith’s though, as ever, take that with a grain of salt - either for smaller wrestling promotions or as a standalone variety act, Smith’s wrestling exploits only made the newspapers or troubled the historical record in the mid-1960s, so a debut date of 1949 seems like yet another tall story, though the occasional billing as “Gorgeous Fuzzy Kaye” at least goes some way to support his claim of working a Gorgeous George-inspired gimmick, even if none of the few photographs I’ve managed to find from his wrestling days support his description of long, platinum blonde hair.

There wasn’t much of a place for “midget wrestling” in the more respectable corners of British post-war wrestling, under the auspices of Joint Promotions, so like Bert Assirati before him and other outsiders before and since, Fuzzyball Kaye had to look elsewhere for his wrestling bookings. Luckily, in Soho, he had another familiar face to turn to.

Though in this case “familiar face” isn’t quite appropriate.

Dr. Death, the King of British Rock ‘n’ Roll

The man to book Fuzzyball Kaye was Paul Lincoln, better known to wrestling fans as Dr. Death, who many old-timers consider the greatest masked man that British wrestling ever produced.

Lincoln started out his career in his native Australia, appearing on small shows and carnival wrestling booths, before arriving in the UK aged 19, and embarking on an unremarkable career for the then-dominant Joint Promotions, and in particular for JP member Dale Martin Promotions. But Paul Lincoln had bigger ideas in mind, and, unable to get the opportunities he felt he deserved from Joint Promotions, turned outlaw and began promoting his own events. With most of the biggest names in the country locked into working for Joint Promotions, Lincoln turned to his fellow countryman “Rebel” Ray Hunter, he repackaged himself as a masked menace from Hollywood, USA, bought a flashy, extravagant office to present an image of high-earning professionalism, and he populated his cards with wrestlers on the outs with the Joint Promotions cabal - men like Bert Assirati and Mike Marino - and with the kind of wrestlers that the ordinarily staid and sensible Dale Martin Promotions shied away from. If Joint Promotions were to sell clean-cut technical wrestling with few frills and gimmicks, Paul Lincoln Promotions would do the opposite - his cards promised midgets, giants, masked men, monsters, brutes, savages, inter-discipline matches pitting wrestlers against boxers and judo experts, and every gimmick you could shake a stick at. Leveraging a business relationship with the Granada cinema chain to provide him with venues to operate, and leaning on friends in the wrestling press to provide publicity, his shows were a resounding success and soon became the talk of the town.

They were such a success that Paul Lincoln soon had more money than he knew what to do with and, like so many of the other characters we have met on this meandering journey, turned to Soho to find somewhere to invest it. Along with Ray Hunter, he purchased a coffee bar named the 2is on Old Compton Street, more for the upstairs rooms to be used for accommodation for visiting wrestlers than anything the coffee bar itself could have offered them.

This was, however, amid the great London Espresso Boom of the 1950s. With fancy new Italian espresso machines becoming available in the UK for the first time - legend has it that the first were smuggled into the country illegally by members of Soho’s large Italian community who couldn’t bear the taste of what passed for coffee in England in those days - it became the done thing for London’s artists, intelligentsia, and anyone who considered themselves part of the in-crowd to hang out in the capital’s trendy coffee shops, a nation weaned on milky tea having their taste-buds and minds blown by rich, jet-black Italian coffee. What’s more, with no alcohol on the premises, these bars were open to all ages, at all hours, free from the vagaries of draconian post-war licensing laws.

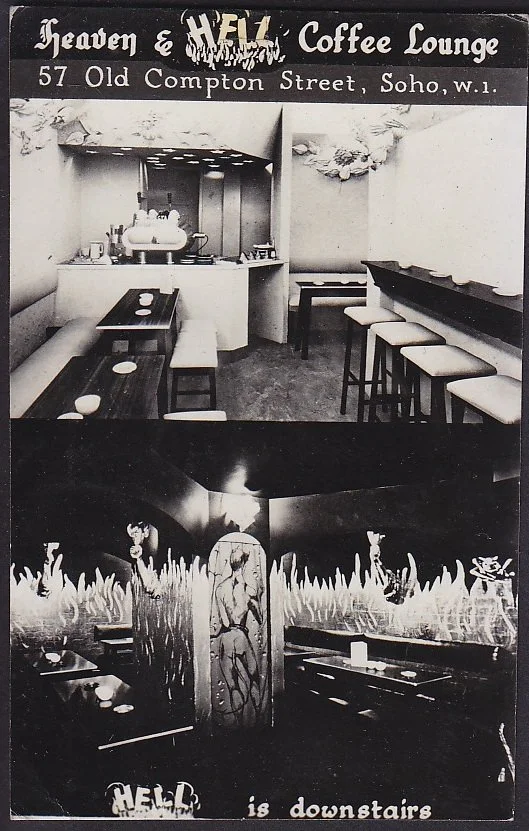

The 2is was struggling to compete in a crowded market of more than 400 espresso bars across London, particularly when the extraordinary Heaven & Hell Coffee Lounge opened next door at number 57 - here, the upstairs room was brightly lit and painted a blinding white, while the basement was dark, painted black and decorated with flames, demons, and red-eyed devil masks.

On 14th July 1956, a group of folk and skiffle musicians calling themselves The Vipers popped into the 2is for a drink during a break in their travelling performance as part of a carnival winding its way through the Soho streets. As they passed the time by strumming out a couple of songs, Paul Lincoln, on a whim, invited them to come back the following week, inadvertently saving his coffee bar’s future, securing his own fortune, and setting off a chain reaction that would come to birth a global phenomenon.

Today, a branch of the consciously nostalgic fish and chip shop chain Poppie’s stands on the former site of the 2is, but prominently displayed by the door is a sign proclaiming it “the birthplace of British rock and roll”, and with good reason.

It was in the basement of the 2is, on a stage built from milk crates, that skiffle evolved away from its earnest folksinger origins, all tea-chest bass, cigar box guitar and washboard, and turned towards electric guitars, Brylcreemed hair, and a ton of wide-eyed enthusiasm. With the British Musicians’ Union all but preventing American talent from performing in the UK, teens chomping at the bit for a homegrown Elvis flocked to the 2is as skiffle begat English rock and roll, and launched the careers of the likes of The Shadows, Vince Taylor, and Tommy Steele. Eager fans rushed from all over to pay their one shilling entry fee, while aspiring pop stars jumped at the chance of free “audition” sets in the hope of finding fame, or attracting the attention of one of the growing number of impresarios and music industry Svengalis frequenting this humble basement, not least among them the future Beatles manager George Martin.

Paul Lincoln himself began to dabble with music promotion and management, while raking in the profits from the coffee shop, and continuing to don the mask of Dr. Death, and promote his own wrestling shows. Life was good for Paul Lincoln, and he never forgot that it was wrestling that afforded him that life.

When it became clear that the 2is needed a bouncer, he of course turned to one of his fellow professional wrestlers, giving the job to a menacing bearded hulk who wrestled under the unlikely names of Count Massimo of Milan and Prince Mario Alassio. His in-ring career was less than princely, but he must have picked up a thing or two from Paul Lincoln and the denizens of the 2is, because in the early 1960s he went into music management, and under his given name of Peter Grant became notorious as the no-nonsense manager for Led Zeppelin.

The success of the 2is was such that Paul Lincoln and Ray Hunter were able to diversify, opening a second branch that was more rock and roll venue than coffee bar, and an Italian restaurant on Old Compton Street, and now they had their sights set on London’s nightclub scene as well.

The Cromwellian was in leafy South Kensington, a good half hour away from our stomping grounds, but it’s a worthwhile detour. Starting out life as - allegedly - an illegal underground gambling den operated by inveterate gambler, zoo tycoon, Lord Lucan associate and avowed Hitler fanatic John Aspinall, it had become a nightclub struggling to sell itself as a society destination when Paul Lincoln came a-calling, along with the ever-reliable Ray Hunter, and one of their closest allies and regular in-ring attractions, the masked White Angel, otherwise known as Judo Al Hayes, and fellow wrestler Bob Anthony, alias Bob Archer. Anthony’s side-line in music promotion earned him the nickname “The Wrestling Beatle”, though sadly he never went the whole hog and embraced the gimmick like American journeyman wrestler Bob Sabre, who briefly adopted a mop-top and the brilliant ring name of “The Wrestling Beatle, George Ringo”. Just like the 2is before it, the Cromwellian was a magnet for the biggest pop stars of the day - the Beatles and the Stones both graced it with their presence, and legend has it that it was there that Jimi Hendrix played, impromptu, his first London gig.

All good things must come to an end, however, and the quartet of wrestlers’ hold on the swankiest of London nightlife was no different. By 1965, Paul Lincoln Management gave up their solitary resistance against the rising tide of Joint Promotions, and merged with their once-rival Dale Martin Promotions for a purported million pound pay-off, taking Dr. Death and his compatriots from the stars of their own show to big fish in a much larger pond. Under the auspices of Joint Promotions, Dr. Death was finally unmasked, by Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson’s grandfather Peter Maivia in 1970, and, disillusioned, he returned to Australia for much of the 1970s and early ‘80s, where he continued wrestling, and opened a private detective agency. Ray Hunter tried his luck stateside with limited success, unlike Al Hayes, who reinvented himself as the snooty Lord Alfred and took to the American approach to pro-wrestling like a fish to water.

But we find ourselves a long, long way from Soho, so let us return, this time, to Hanway Street, a narrow thoroughfare branching off from the sardine-pressed tourist hustle and bustle of Oxford Street, to find Bradley’s Spanish Bar.

It’s All Greek To Me

I will admit, this place was utterly unknown to me and to my mental map of Soho until I landed on the excellent history written by John Bull during the Covid-19 pandemic. It was only right, then, that I held off on sampling the delights of Bradley’s until such time that I could drink in there with John himself, which I did when I began writing this tipsy travelogue.

The exterior of Bradley’s Spanish Bar, as inexpertly photographed by the author

From the outside, Bradley’s could be, despite the garish signage in Spanish flag colours, easy to miss. It’s entirely incongruous so close to London’s busiest shopping streets; the combination of simple signage and a name that jars with what one would expect from English pub naming conventions - no White Harts, Red Lions, or King’s Arms here - from the outside it put me in mind of the tinier and rougher around the edges pubs I’d visited in Malta, or the no-frills bars serving British ex-pat communities in the South of Spain. If I hadn’t been primed with knowledge of its history, it’s a pub I would have walked past ninety-nine times out of a hundred, barely allowing its presence to register. That would have been a mistake.

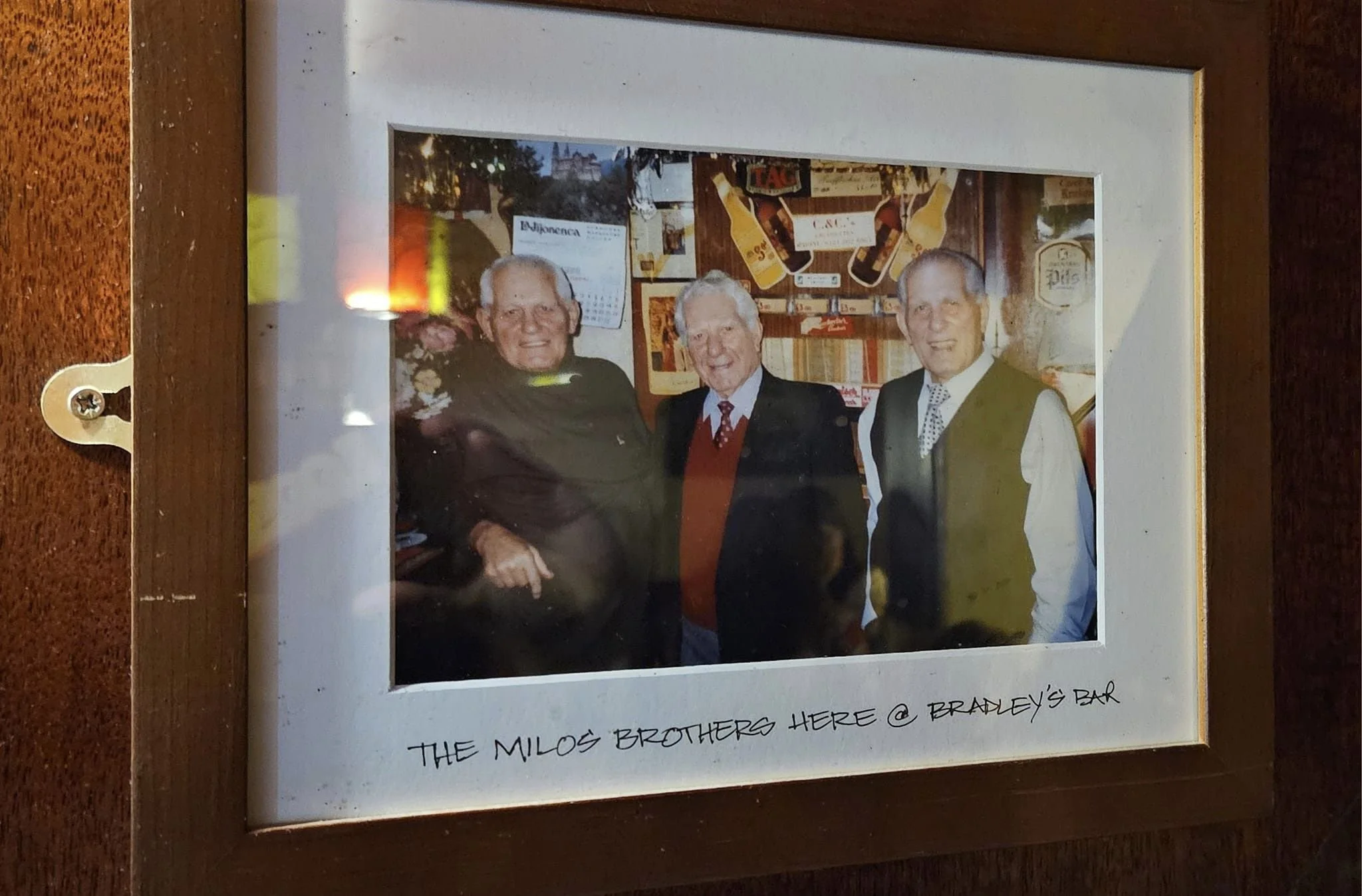

Inside the tiny basement bar, it became clear that this was my kind of establishment, a Paul Heaton song playing as I entered, and where the veil separating regular and newcomer is roughly as thin as one pint and the ability to hold your own in good conversation. Within a couple of drinks, John and I were sharing Soho stories and well-honed jokes with long-time barman Rich, and the Jägermeister was flowing as fast as the chat, both coming perhaps a little too easily for a Thursday evening! This was a pub I could get used to and there, discreet among its décor, was exactly what I had come here to discuss - a framed photograph of three unassuming elderly man, captioned “The Milos Brothers here @ Bradley’s Bar”.

Three Greek-Cypriot brothers, none of them called Bradley, none of them remotely Spanish, were the brains behind Bradley’s Spanish Bar. But to confuse things a little further, none of them were called “Milos” either, not really.

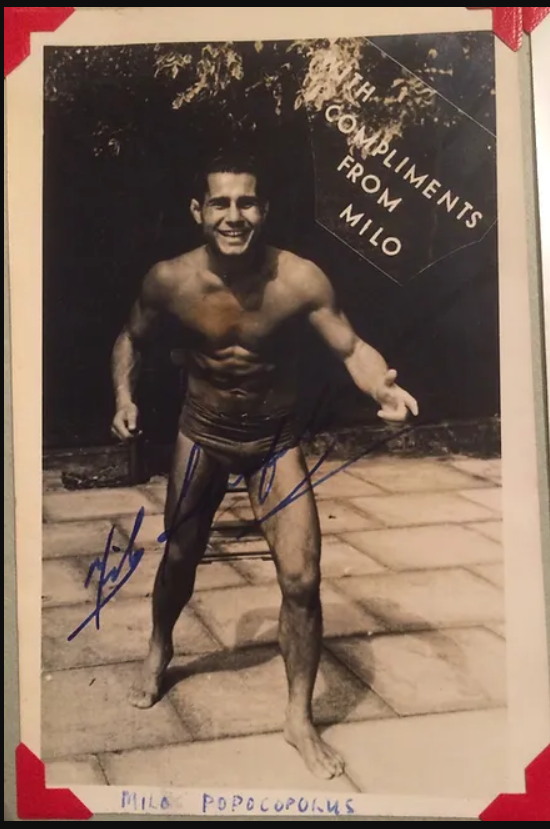

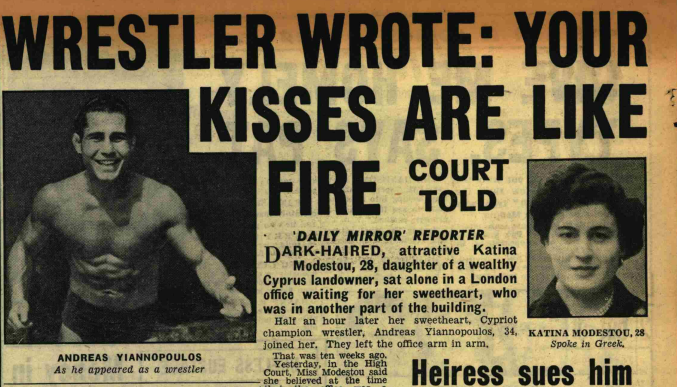

They were, as you must have guessed by now, professional wrestlers. The oldest was Milo Popopocopolis - or Popocopolis depending who was writing copy for the poster - and all three of them, at one time or another, took the well-worn nickname “The Golden Greek”. For good measure, Milo’s birth name was actually Andreas Nicola Yiannopoulos - smarmy far-right agitator du jour of the 2010s Milo Yiannopoulos is apparently a distant relative, via his step-father - and he had no shortage of other pseudonyms, but it was likely younger brothers Johnny and Tommy both adopting “Milo” as a surname for their own in-ring endeavours that ultimately settled it as the family patronym, though perhaps with a nod to Milo of Croton, the Ancient Greek wrestler of legend.

Milo Popocopolis may have had some wrestling experience prior to his arrival on English shores, but the first record of him competing professionally is in 1937, competing in Hull at the age of sixteen, supplementing the wage he made as a dish-washer in a hotel kitchen. For the time being, his wrestling career remained in the North and Scotland - where, for Relwyskow Promotions, he competed as Andrea Nicola or “Driver” Nicola; an allusion to a military rank, an easy route to babyface appeal in the early 1940s, though whether Milo ever actually served is a mystery. By the time the War was over, Milo had cemented himself as a contender, appearing for most of Joint Promotions’ most prominent members, competing for championships, and wrestling the likes of Jack Dale (along with Les Martin, the namesake for Dale Martin Promotions) and Bert Assirati, the stars of their day.

As a suitably boozy aside, Wrestlingdata.com lists Milo’s last match in 1965 against John “Killer” Kowalski. Aside from his more famous American namesake, his was a name I was unfamiliar with, until a regular at my local pub happened to mention to me that his friend’s father had been a wrestler, and proffered the name Killer Kowalski. After the slightest bit of research, I found his name and a career that took him all over the world, including to NJPW in their inaugural year - in those moments of serendipity and synchronicity that occur to every researcher, I now encounter his name seemingly everywhere I look.

By the 1950s, Milo had landed in London, and there he would remain, by the middle of the decade having bought into any number of hotels, bars and other businesses. Now joined by brothers Tommy and Johnny, Milo had become a regular fixture for Paul Lincoln Management. In 1952, riding the same coffee shop fad that had sent Paul Lincoln to the 2is, the younger Milo brothers set up shop in the Acapulco coffee bar, where the kitschy Spanish theme became an unlikely catalyst for Soho to develop it’s own lively Spanish quarter. That would be a “Spanish” coffee shop run by Greek-Cypriots - oh, and just as an extra measure, it was decorated by wrestler-cum-decorator “The Golden Greek” Mike Demitre who was, of course, Canadian. In the world of wrestling, names and nationality are things to be tried on and discarded, changing as freely as your mood.

By 1969, the “Milo Brothers” had taken ownership of Bradley’s Spanish Bar, on the same tiny street as the younger siblings’ coffee shop. It was named for William Bradley - more of that explanation in the aforementioned John Bull piece - but it was Milo and his brothers who built this tiny pub into a social hub, and the kind of place that, even decades later, would lure the likes of me through its doors, and keep us happy and well looked after for as long as we wished to stay.

Back in the ring, Milo was a star not only for fellow Soho denizen Paul Lincoln, but for the trailblazing Kathleen Look, the indefatigable matchmaker for the Belle Vue in Manchester, and for a brief time for venues in Brixton, likely the country’s first female wrestling promoter. Milo also tried his hand at promoting his own shows in London and Hastings with some success, and was a proud paid-up member of the Wrestlers Welfare Association, an early attempt at a wrestlers’ union, even going on strike for better pay and working conditions!

Milo’s personal life was sometimes as dramatic and chaotic as his wrestling, and as muddled and confused as his business operations sometimes appeared, given that in 1954 he was up in court, eventually having to pay £5000 in damages (equivalent to in excess of £110,000 today) to a Cypriot socialite he had, apparently, somehow fraudulently convinced he had legally married. No such marriage had taken place, and in fact Milo was already married, and this was just one of a run of ill-fated affairs - the judge, as damning as he was accurate, deemed that Milo had behaved “like a cad”.

The elder brother may have behaved like a cad in his personal life, but the Milo Brothers were gentlemen in their professional role as custodians of Bradley’s Spanish Bar, and the community of drinkers that grew around it, even if they were happy to play fast and loose with questions of nationality and identity; I’ve come across multiple accounts on social media from former patrons sharing memories of the 1980s and ‘90s, who refer erroneously to the landlords as “elderly Spanish wrestlers”, and one can perhaps forgive the confusion, stemming as it does from this decidedly un-Spanish Spanish Bar.

Maybe that’s at the heart of all of this - that for these wrestlers, as it had been for my friend Twiggy, Soho was a place to find oneself, but also to find a little fluidity in the question of what the “self” was. It was a place where Greek wrestlers could become Spanish, where a Polish Londoner could turn the scars of a gangland assault into the mark of honour of an aristocratic Nazi villain, where nicknames became names, where a homeless dwarf ex-wrestler could spin yarns about Hollywood stardom and gangland adventures, and where a good story and good company would always carry more weight than such trifling concerns as the truth or the law. In Soho, you could be anything, so long as you were never boring.

Last Orders

Many of the locales we’ve visited on this boozy bimble are now closed, and most of the principle players are long gone. The denizens of Soho have been bemoaning the death of the district for decades but today it’s difficult to shake the thought that they might finally have a point. The clubs and pubs make way for identikit office blocks and chain stores, the characters and eccentrics of yesteryear supplanted by marketeers, tourists, and hen parties, and all that’s left to honour the wrestlers of old Soho are a plaque outside a chippy, and a photo of three old men in a basement bar.

A facsimile of the Colony Room Club was opened on Regent Street, a perverse experiment in preserving in aspic a moment in time that breathed its last more than a decade ago, just as distasteful an exercise in gentrifying and commodifying the counter-culture as renting out Sebastian Horsley’s sleazy living quarters to eager tourists with money to burn. Pubs like the French House and Bradley’s barely survived the Covid-19 pandemic, having to resort to generous donations from the public to keep their doors open. As the cost of living crisis - in reality, a cost of greed crisis - shows little sign of abating, and more than 500 pubs closed in 2023, with London venues closing at a faster rate than the rest of the country, neither public houses nor their public can afford to keep digging deep to help each other out, and we will all suffer as a result. After years of false alarms, it seems inevitable that last orders will be called for old Soho sooner rather than later.

As for my friend Twiggy, Soho’s decline and the loss of its boldest and most visible characters was a problem closely felt. Coming soon after the death of Sebastian Horsley, in a rare unguarded moment of vulnerability, I saw Twiggy almost inaudibly whisper, “I do miss him” to no one in particular. To Twiggy, and to many around him, death was always around the corner - a lifestyle like his made it hard to shrug off - but, borrowing a metaphor from Jeffrey Bernard, he always felt most hurt by it when it seemed like younger Soho denizens were jumping the queue, and leaving before it was their turn.

Twiggy’s turn eventually came, when last orders were called in January 2018. While he may not have feared death, and was prepared to face it bravely, it’s a thing that rarely comes unbidden, and the months and years before it were not pleasant. My visits to see him became less frequent as he became less able to brave public transport and make it to the French House - on a cocktail of painkillers and sleeping pills, and at risk of losing his leg, towards the end he spoke of little else but his pain. The walking stick he had come to use the last few times I saw him had given way to a mobility scooter he christened the “Cuntmobile”, but soon even that was too much for him to manage. His last days were unbearable to watch, even from afar. I miss him still, and it was years before the dreams of him showing up unexpectedly to the pub, revealing the whole thing to have been a ghastly misunderstanding, abated.

From time to time, I still return to the French House. It was there where Twiggy first welcomed me into the world that his anecdotes had set the stage for, and today a framed photograph of him hangs behind the bar. It’s an anchor, a point of reassurance, when life can feel overwhelming, somewhere to turn when I feel lost and unsure of myself. It’s tiny, often as full of confused tourists as it is of character, and there’s only two days a year that you can order a pint of beer rather than a half, but I love it all the same. Having recently returned to Bradley’s for only the second time, I can already feel myself developing a similar affection for Milo Popocopolis’ old haunt.

I hope you’ll forgive the autobiographising of this piece; it is hard to articulate what Twiggy meant to me, and the gifts he was able to give me in life, without mythologising and romanticising a few old pubs and one old piss-artist to a near-absurd degree. But his greatest gift was that, with all his star-studded anecdotes and wild stories, Twiggy could easily have been a show-off and a braggart, but he never treated me or anyone else he took a shine to as a tourist or an interloper in his old world, only ever as an equal who belonged there as much as anyone.

He always wanted me to write, and while he might not have been particularly enthused by the subject matter that I eventually did turn into a book, I’d like to think that he would be proud of my efforts. I often expressed an interest in him writing his own memoirs, but to him life was to be lived, and someone else could write the story once the subject was no longer around to get in their way. He asked that, given the opportunity, I should write his obituary, so long as it ended with one phrase. So here goes:

The next one’s on me, you fat old cunt.

Update - 5th November 2024:

Last week, footage finally emerged of George Hackenschmidt wrestling Joe Rogers at the Oxford Music Hall. That location wasn’t included on my Soho wrestling pub crawl/walking tour, but if you wish to pay your respects, it’s now the big Primark on Oxford Street, so you can always give it a nod on your way down to Bradley’s. Honestly, there should be a blue plaque.